On the evening of November 30th, the Urbana Civilian Police Review Board (CPRB) assembled for an appeals hearing on a CPRB complaint in regards to an incident that occurred over one year ago. The board quickly moved into closed session, and the information presented here comes from the appellant.

The issue of procedure quickly arose, since the appellant questioned the proposed procedure wherein the CPRB would hear testimony from the appellant and the Urbana police representatives separately, but the two parties would not be able to hear each other’s statements. The only advantage to this approach may be that keeping the police and City representatives out of the room while the appellant is presenting would remove the intimidation factor for the appellant. However, given that the appellant, the only regular member of the public present, was the one suggesting that everyone stay in the room for the entire hearing, that was not a factor.

The appellant’s reasoning for this was very simple: the CPRB has not in any way demonstrated that it is capable of identifying misconduct, and that burden is therefore placed squarely on the appellant. This has been made abundantly clear by the history of the CPRB, and for a recent example of a violent incident that received a thumbs-up from the CPRB, the reader may view this article: Urbana Police TASER Video Shows Blatant Misconduct…

City Administrator Carol Mitten was quick to argue “on behalf of the City”. Mitten argued that since the hearing was being done in closed session, every effort needed to be taken to ensure that the session remained confidential. Again, it would seem that the only person who should be given privacy considerations is the civilian appellant. Everyone else present was acting on behalf of a public body.

What Mitten said next was rather disturbing: “The city has abilities to sanction everyone in the closed session, with the exception of the appellant”. Mitten said that the appellant can’t sign away their rights and it is their First Amendment right to repeat what they hear in a closed session (as was done to produce this article), but that the CPRB members could be sanctioned to prevent them from ever disclosing what was discussed in a closed session. In this context, when Mitten says “sanction” she means that the City would take legal action to effectively gag a public board member and penalize/fine them for speaking about a closed session.

Mitten said that keeping the appellant out of most of the closed session “maximizes the protections of the closed session.” Ultimately, the entire closed session portion of the night’s meeting lasted just under 3 hours. The appellant was allowed into the closed session for about 48 minutes of that time, and only 23 of those 48 minutes were spent actually talking with the CPRB members about the complaint. For the other 2 hours of the hearing (about 15 minutes at the beginning and the balance at the end), the appellant sat in a Zoom “waiting room” staring at a blank white screen, not having any idea what was happening or when they would be summoned again.

The problem with Mitten’s contention, besides the fact that it results in the complaint process being even more upsetting and useless for complainants, is that legally, the City of Urbana cannot threaten or enact sanctions upon its board members for disclosing information about closed sessions. The City simply does not have the power to do so, and Mitten’s axiom for concealing the bulk of the hearing proceedings from the appellant is simply wrong.

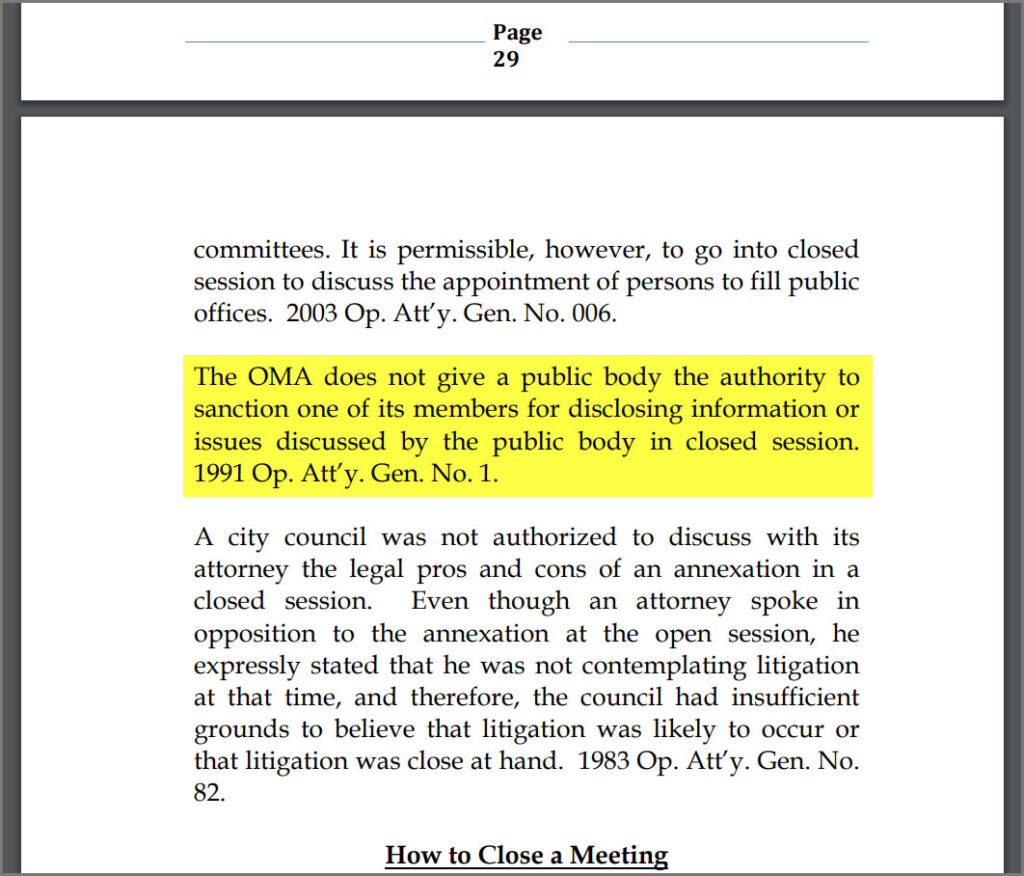

This issue is not new and should not be contentious. Illinois Attorney General Roland Burris authored a determination letter to the State’s Attorney of Kendall County in 1991 which explicitly dispenses with any notions that public bodies have the authority to sanction its members for disclosing information about closed sessions. Burris went as far as to say that such sanctions would be “an absurd construction of the law”. Here are some clips from his determination (which you can also view in its entirety here):

“I have received your letter wherein you inquire whether a public body has the authority to sanction one of its members for disclosing issues discussed by the public body in a pursuant to sections 2 and 2a of the Open Meetings…For the reasons hereinafter stated, it is my opinion that public bodies do not have such authority.”

“There is no provision in the constitution or the Open Meetings Act which expressly authorizes public bodies to sanction their members for revealing what went on during a closed meeting, and there is clearly no constitutional provision from which one may imply such powers.”

“In general, the Open Meetings Act does not confer power upon public bodies. The Act assumes, of course, that members of public bodies must meet to conduct business and it requires that such meetings be open. The Act authorizes public bodies to hold closed meetings for specified purposes and authorizes a public body to prescribe reasonable rules governing the right guaranteed by the Act of persons to record open meetings…Nothing in the Act is to be construed to require that any meeting be closed…and the purpose of the Act is to ensure that the actions and deliberations of public bodies are open to public scrutiny…Thus, there is no power conferred by the Act to which the power to sanction members is a necessary incident; moreover, there appears to be no objective from which the existence of such a power could be necessarily implied.”

“Indeed, the implication of such a power would clearly work to subvert the purpose of the Act…Such an absurd construction of the law, which would render ineffective the public policy of this state favoring openness in government, must be avoided.”

There was also an appellate court case in 1990, Swanson v Board of Police Commissioners of the Village of Lake in the Hills, which arrived at the same conclusion. Here is the relevant part of the court’s decision (read the entire decision here):

“Swanson contends the Board violated the Act because it made various disclosures to the public concerning information made in closed session…there is no provision in the Open Meetings Act that applies to the action about which Swanson complains. The Open Meetings Act is aimed at guaranteeing public access to meetings of governmental bodies…It also allows governmental bodies to meet in closed session in certain situations…There is nothing in the Act that provides a cause of action against a public body for disclosing information from a closed meeting.”

Even the Champaign County “OMA Reference Guide” (http://www.co.champaign.il.us/FOIA/OMA_Reference_Guide.pdf) makes this point clear:

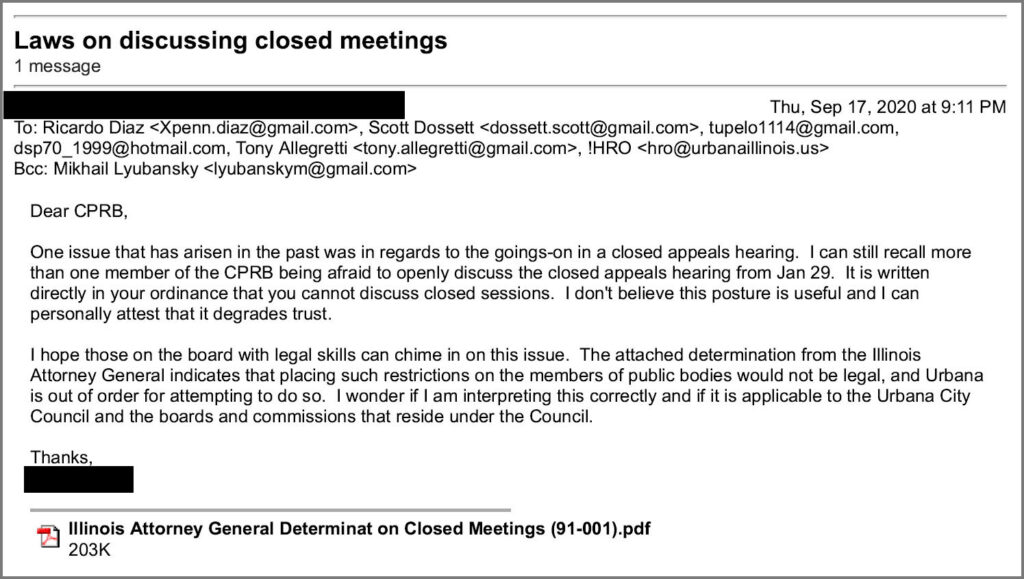

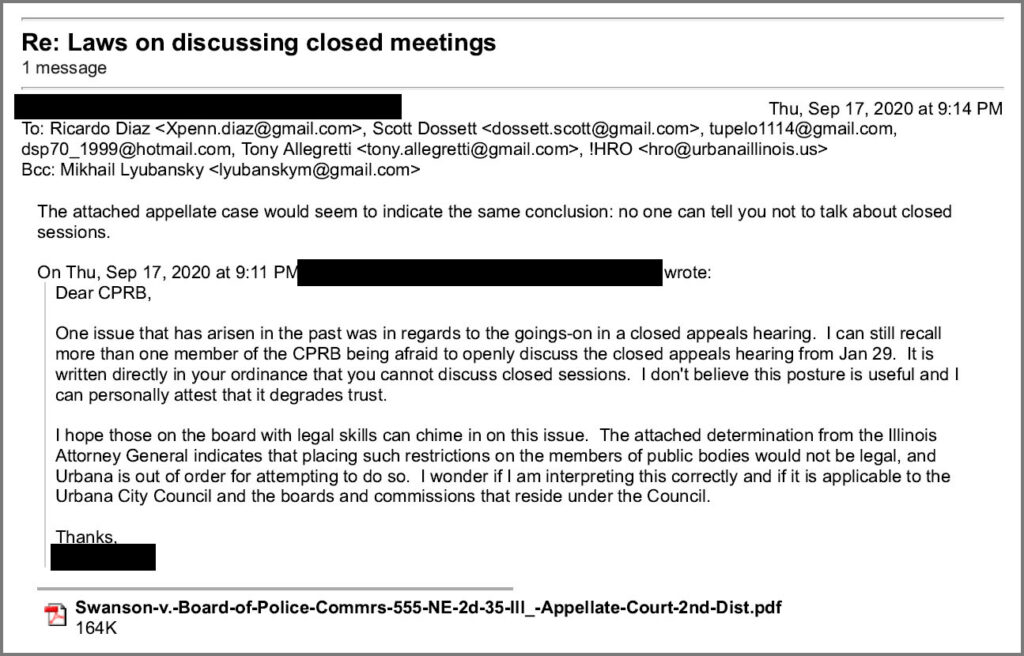

Having already anticipated that City staff would try to censor board members, the appellant had attempted to deal with this issue more than two months prior to the November 30th hearing. They sent an email to the CPRB members and Urbana’s Human Relations Officer (a role apparently assigned to Mitten as of late), which included the Attorney General determination cited here. The appellant then sent a follow up email including a copy of the Swanson case cited in this article. Not a single board member or City official responded to those emails.

The same emails were sent again to the CPRB members during Monday’s hearing, just minutes after Mitten spoke about sanctions. Two days later, still no one has responded, which is, unfortunately, very typical of the CPRB.

It is worth noting that CPRB member Tony Allegretti is a licensed attorney and CPRB member Darrel Price is a recently retired state prosecutor. It is entirely reasonable for them (and the other board members) to contemplate simple legalities such as these. It remains a mystery why a board designed to scrutinize the actions of City employees seems so content on marching to the tune of the City legal department which has so frequently led Urbana astray, both legally and ethically.

Though not terribly significant in function, but greatly significant in the message it sends, the coup de grâce of Monday night’s meeting was when the CPRB took a motion and vote within the closed session. They wanted to take a vote to leave the closed session. The appellant explained to them that the Open Meetings Act doesn’t allow this and that they needed to return to the public meeting to take that motion and vote in public view. But they wouldn’t listen. Darrel Price even argued that the vote should be taken within the private session, which is a clear OMA violation. Neither of the licensed attorneys in the closed session (Allegretti and the hired hearing officer, Alyx Parker) said anything about the closed session vote.

In addition to being an Open Meetings Act violation, this also exemplifies the CPRB’s chronic inability to consider input and make accurate determinations. In the midst of a hearing specifically about misconduct, the board members could not even hear and responsibly consider their own procedural blunder, no matter how much expertise was present.

In addition to problems generated by actions taken, and not taken, by individual members of the CPRB, the public has repeatedly seen from the board an apparently willful blindness to the attempts of City staff to hamper and obstruct the police complaint process. This has been demonstrated time and time again as the board looks the other way, defers responsibility, and capitulates under pressure from City and UPD command staff. The CPRB remaining silent and compliant in the face of the City’s unlawful threat to punish them with sanctions should they disclose issues or information discussed during closed meetings is just the latest deplorable example.

Mitten’s threat of sanctions upon Urbana board members is wrong both legally and morally. Intimidating and gagging our public board members is not productive, and it is exactly the type of censorship corrupt governments engage in when desperate to keep a grip on their instruments of power.

For more recent efforts to censor the public, the reader may be interested in this article: Urbana’s Solution to Police Misconduct: Secrecy and Censorship

Brave exposé of the lies and coverups with which the City is swaddling misconduct and corruption at the UPD – and the CPRB’s quiet compliance.